“I had been about ten days at the front when it happened. The whole experience of being hit by a bullet is very interesting and I think it is worth describing in detail.”

-George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia

During my time as a reporter in Cyprus, no writer influenced me more than Orwell. A four-book compilation of his essays and correspondence that I chanced upon at a Nicosia pop-up used book sale was my de facto journalism school.

I was gripped by his clarity and independence of thought, by his brisk and punchy sentences free of those multisyllabic convolutions and eye-glazing turns of phrase ubiquitous to academia and corporate speak, and, above all, by his unique faculty at calling out lies and propaganda. The man could litigate against bullshit like no one else.

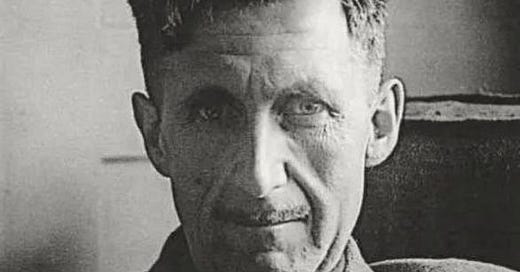

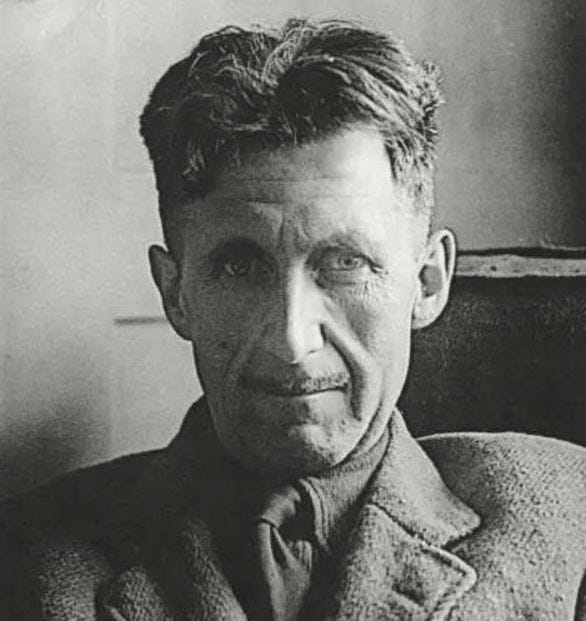

When I look over the essays I wrote during those years, and even those I still write, I often see him winking up at me. I say ‘winking’ because, though by all accounts he projected a sad, lanky, consumptive figure in person, his writing brims with characteristic English wit. You even see this in portraits of him, a wry smile peeking out through that gaunt lined face.

The critic Lionel Trilling once remarked of Orwell that he’s important precisely because he’s “not a genius”: he is tangible proof that any of us, with some moral and physical gumption, have the capacity to do what he has done. If we fall short, it’s only because we are cowards who lived poorly, who lacked what Orwell called a “power to face unpleasant facts.”

For sure, Orwell lived and wrote about life head on. He was no off-site activist—no urban liberal who holds easy views agreeable to the neighbors, no slick jingoist who never dirtied a fingernail, never mind shouldered a gun.

No, he was both oppressor and resistor. An Eton-educated schoolboy, Orwell (then Eric Blair) rejected an Oxbridge future to instead serve as an imperial policeman in Burma. There, he saw up close the degradations of empire and felt its corrosive impact.

Reneging that role too, he returned to Europe. But he remained a rogue to his social class, opting to live as a vagrant for a spell so that he might know in the stinking flesh the realities of the unwashed masses.

Even as an intellectual he was an outlier. Ivory tower insularity wasn’t for him: he didn’t just opine on fascism, he volunteered to fight against it.

In the Spanish Civil War, a sniper shot him through the throat (literally ‘through’—the bullet entered one side and exited the other). As he was carried off on a stretcher, blood bubbling from his lips, he assumed those were his final moments. Only later would he learn that the bullet had missed his carotid artery and spinal column by millimeters.

Though it took him months to recover, the only permanent damage was to his vocal cords, leaving him hoarse for life. It was as if the fascist sharpshooter had the prescience to recognize that, even if he didn’t kill this sunovabitch, he’d better at least silence him.

Alas for the totalitarians and their heirs, he wasn’t silenced. Much like the deafness of Beethoven and the blindness of Borges, which fueled rather than debilitated their art, Orwell’s lifelong rasp similarly found counterpart in a lucid and resounding authority in print.

Not that his voice was fully appreciated for all but the last four years of his life. Even then, his relentless broadsides on the orthodoxies of his time (imperialism, fascism, capitalism, Stalinism… pick your jism) led to him having as many haters across the political spectrum as he now has devotees.

A political heterodox, he was a rogue to the left in his condemnations of Soviet communism back when Stalinism was trendy, and to the right in his invectives against capitalist exploitation and inequality.

Most important, he was a rogue to all forms of groupthink. He resisted ideological capture, refusing to let his mind become a vessel for the mush of propaganda. Instead, he had the audacity to openly say what he believed even when that made him a pariah.

In recent decades, of course, everyone from neocons to antiwar protestors, from CEOs to anarchists, from prime ministers to political outcasts, has pressed their cases in his name, even though their ideological counterparts in his time would have disparaged him.

Were he to reincarnate momentarily, he’d surely be the first to shake his head at the, shall we say, Orwellian nature of all this contemporary idolatry. As he said in his essay on Gandhi, “Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent.”

He’s now such an institution—arguably the Shakespeare of political writing—that it is hard to imagine the realities of his life. His essays were not widely read. Homage to Catalonia is now considered one of the great works of war reporting, but in its first six months of publication it sold under 700 copies, and by the time he died, the initial print run of 1,500 copies had yet to be exhausted.

The world wasn’t ready for him. He was, to use a cliché that Orwell would no doubt abhor, ahead of his time.

Of course, in our time—even if we overlook as maladies of his day his homophobia and myopia towards women—he wouldn’t last long. A swift cancellation and public flogging would surely follow. But he would also, no doubt, give us a splendid account of what it’s like to be deplatformed.

Yes, Orwell matters. It’s not just that reading him is fun, though it is that too. It’s that in reading him, you fortify yourself against censorship, saber-rattling, and doublethink—that uniquely homo sapiens ability to hold two contradictory views simultaneously. And these authoritarian regressions are all staging a comeback, not just in the usual suspects, but chiefly and devilishly among those who most loudly profess themselves the defenders of democracy.

Though renown finally came with Animal Farm, his last few years were far from joyful. He wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four amid severe illness. The novel was published only months before he died alone in a hospital bed at the age of 46, hemorrhaging from tuberculosis, a quintessential poor man’s disease. As I have now mysteriously found myself deep into my forties, this grim biographic fact did, I confess, prompt in me a mini mid-life (end-of-life?) crisis and a kick in the ass, which I do always welcome.

No recordings of Orwell’s radio broadcasts or readings survive. But we have his essays. Here are a few launching-off points:

For the writers: Why I Write

For the news junkies: Politics and the English Language

For the perfectionists: A Nice Cup of Tea

And even if you’re not a writer, a news junkie, or a procrastinator, you’ll be well-served by all three.

If nothing else, as you scroll through the latest NYT op-ed, always keep present at the back of your overcultivated brain Orwell’s admonition: “One has to belong to the intelligentsia to believe things like that: no ordinary man could be such a fool.”

George Orwell. 1903-1950. Rebel with a Cause. Straight Shooter. Heroic Everyman. Tea Snob.

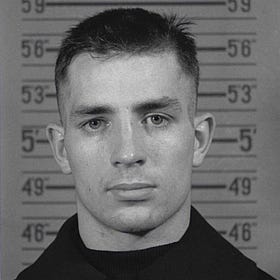

Rogue 1 - Jack Kerouac

“An awful realization that I have been fooling myself all my life thinking there was a next thing to do to keep the show going and actually I'm just a sick clown and so is everybody else..." -Jack Kerouac, Big Sur In the hardy cast of twenty-year-old Kerouac in this naval enlistment mugshot, one already sees the rugged, straight shooting vitality of

Did not know all this about Orwell, even though I had read both his "big hits" while in school. Thank you for this very interesting essay. Loving your "Rogues Gallery".

Found Orwell and Huxley within the last year. Maybe finally maturing as I round 50. I enjoyed getting a deeper perspective into who he was, and how he influenced you. "Fortifying yourself against censorship, saber-rattling, and doublethink... these authoritarian regressions are all staging a comeback." Well said. Influence the group, and be aware of the group influencing you. A rabbit hole I think is healthy to wander into often. Thanks for taking the lead on this trip.