Read the first half here:

The God of War in Lebanon (Part I)

Then looking at [Ares] darkly Zeus who gathers the clouds spoke to him: “Do not sit beside me and whine, you double-faced liar. To me you are the most hateful of all gods who hold Olympus. Forever quarrelling is dear to your heart, wars and battles. […]

Part II: The morning after

Aug 14, 2006

I threw on shorts and a shirt and dashed to the rooftop. There was still an hour and a half until the ceasefire. I saw no smoke, but looking up, I noticed what looked like a flock of sparrows swirling in the morning sun.

Leaflets.

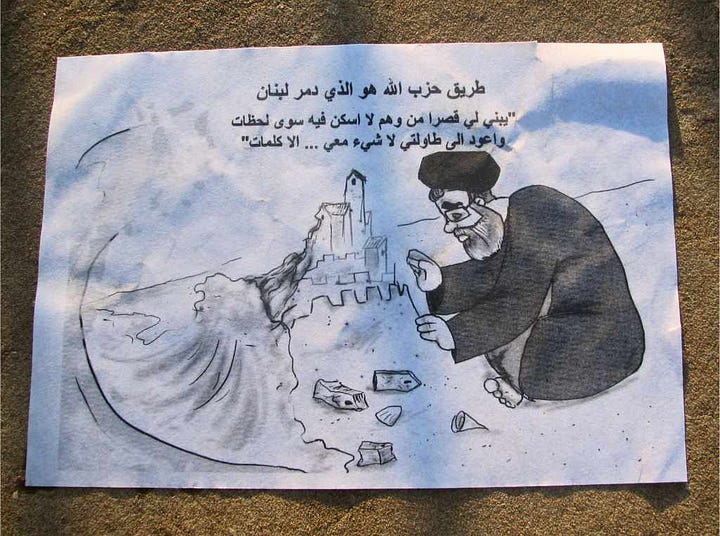

Israel often drops leaflets depicting cartoons of Hezbollah’s leader, Nasrallah, as a snake or scorpion, etc., but they also sometimes drop P.R. leaflets warning of an impending attack.

As I watched them flutter down, I thought only of the warning leaflets. Perhaps the guide had been right after all. It would be a dramatic way to herald the ceasefire, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to be part of that drama.

Had I been coolheaded, I would have instantly recognized that—unless the ceasefire had been cancelled—it would be absurd to imagine Israel would drop evacuation leaflets only to bomb an hour later. But due to inexperience and tingling nerves, I had grimly made up my mind that F-16s were on their way.

I lunged at the first leaflet, clutching at air as it whisked by the building. Neighboring residents were doing the same from their balconies.

Another leaflet landed in the center of the rooftop pool. As the pool was the size of a large tub, I was able to fish the leaflet out by extending a leg. It was a cartoon of Nasrallah making a sandcastle as a giant wave approached. At the top, there was some Arabic writing, which I couldn’t read.

This did not look like a call to evacuate. But as I was crouched, another leaflet fell on my shoulder. On it were several paragraphs of incomprehensible and, for that reason, ominous text.

I returned to my room and switched on CNN, the only English-language news station. It was a live broadcast from Beirut. On the screen was a photo of the same leaflet in my hand with the headline, “IDF leaflets: army will return if Israel is attacked.”

So there was no bombing imminent.

It is a curious irony of modern technology that, even as the leaflets were falling on my head, someone reclining 6,000 miles away with a beer in one hand and a remote in the other knew more about their content than I did. That said, it is also an irony of modern propaganda that the facts presented to him in such a timely manner will—due to the ideological platter on which they are dished up—mostly serve to misinform.

Though the previous day had seen the heaviest shelling by both Israel and Hezbollah, the strikes abruptly ceased at eight a.m.

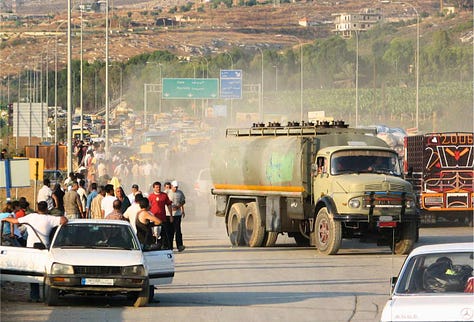

The population did not wait to see whether the ceasefire would hold. At once they were out, traveling to the most heavily bombed places to see whether their homes, and in some cases neighborhoods, still stood. The roads heading south—completely deserted just yesterday—were now bumper-to-bumper with cars loaded down with mattresses and plastered with pictures of Nasrallah.

The day after the ceasefire, the Secretary General of the Lebanon Branch of the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS), Dr. Mohammad Osman, drove me and the two members of the Cyprus MDM to visit a hospital and refugee camp in the port city of Sidon (Saida), normally a 40-minute drive south from Beirut.

The drive took over three hours. Had we stayed on the coastal highway, it would have taken longer, but we bypassed the heaviest traffic and bombed-out bridges by detouring through winding mountain roads.

Even there, the roads were congested. Dozens of cars were stranded on the curbside from overheated engines or lack of petrol—a scant wartime commodity that Osman had astutely stocked up on.

Everyone I spoke with in Lebanon affirmed that the devastation over the last month was greater than anything from the 1982 Israeli offensive or the 15-year civil war. The more I saw, the more I believed it. Almost every bridge we encountered, especially along the major highways, had been damaged or destroyed.

The previous day Osman had taken us to the outskirts of the southern suburbs of Beirut and pointed out a ruined apartment building that appeared to have been strafed with heavy gunfire.

“This is my house,” he had said. “It wasn’t hit, but the buildings beside it were.” Shrapnel alone had wrecked his building. Those directly hit were now mounds of rubble. We lingered in the car at the foot of the pockmarked building. “I hope the furniture isn’t damaged,” he mused, then shifted into gear.

His office at PRCS headquarters had fared better. Aside from the windows, which had collapsed inwards after a missile struck a bridge several hundred yards away, the building remained undamaged. In southern Beirut, it was a stroke of good fortune if your building suffered no more than shattered windows.

At one point during the drive south, Osman glanced at me through the rearview mirror. “Is the wind too much? I can roll up my window.” I told him I preferred the wind on my face. He nodded. “I’ve gotten in the habit of keeping the windows down so that they don’t break if a bomb falls nearby.”

Upon our arrival in Sidon, the first task was to secure permission from the Lebanese government to enter the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp. Cyprus MDM had packed and shipped 21 pallets of clothing from Cyprus, which we had helped load onto two trucks at the Beirut port the previous day.

Fifteen of those pallets were for the refugee camp. Osman waited at the Al Hamshari Hospital while a young woman named Nesrine helped us complete the paperwork. Then she escorted us to the fortified eastern camp entrance.

Even with government approval, the Lebanese soldiers nearly denied us entry. They initially offered a vague nonsensical reason and then claimed it was because I was a journalist.

A ten-minute row ensued between the soldiers and Nesrine, who refused to turn back. Just when I thought they might haul us out of the van, they grudgingly waved us through.

I gathered that the complication was partly sheer harassment, partly security concerns. The Lebanese army does not enter Ain-al Hilweh, and the Lebanese authorities have no presence there.

Though the refugee camp spans only 1.5 square kilometers, it houses about 70,000 refugees, making it the biggest in the country. It opened after the 1948 war, when over 100,000 Palestinian refugees sought shelter in Lebanon. As Nesrine said, “There are people who are born in Ain al-Hilweh and who die in Ain al-Hilweh.”

It would not be until the following morning, while doing background research for an article, that I began to understand why gaining entry had been challenging. Ain al-Hilweh is regarded as a hub of Palestinian resistance against Israel, with various armed Palestinian factions allegedly running the camp and fighting one another for control of various neighborhoods.

Due to its unmonitored status, many believe that wanted militants and terrorists hide out there. Some went so far as to even call Ain al-Hilweh the “single most important al-Qaeda base of operations in the Middle East.”

Osman, on the other hand, maintained that while the camp was once a hotbed of militancy, it had quieted down recently. Whatever the case, what was certain was that Ain el-Hilweh, or “sweet natural spring” in Arabic, was an overcrowded and impoverished concrete shantytown.

Our first stop was a school converted into a temporary shelter for displaced Lebanese. New friends, whose bonds had been forged under wartime duress, hugged and wept before being bussed back to their homes in the south.

Nesrine introduced me as a journalist, and I was immediately besieged. I became a vessel through which they might communicate their hardship, sorrows, and fury to the world.

“We want the United Nations to not only give us schools and food,” said one man who might have pursued a diplomatic career under different circumstances, “but to also oblige Israel to respect international law and not only Resolution 1701 but also other resolutions because—” and while I stood nodding and scribbling in my notepad, someone else would shout at me, “Israel has only killed civilians, but Hezbollah only kills Israeli soldiers, not a single civilian!” an absurd claim, but I just went on nodding and scribbling—to each their propaganda—no longer even aware of what I was writing because I was thinking about a photo I wanted to take of two women in tearful embrace.

Amidst this chaos, I heard someone mention Israel had bombed the refugee camp just before the ceasefire.

I asked Nesrine if this was true. She confirmed it. Could we visit the site of the attack? No.

I instantly grew suspicious. I didn’t dismiss the possibility outright, but I knew distortion and fabrication are rampant in wartime.

My suspicions proved wrong. After delivering the 15 pallets of clothing to the community health center, we had spare time, so we headed to the site of the attack.

I won’t forget the moment I turned the corner and saw the row of smashed up cars and the parking lot of rubble. The cars had been crushed in the fountain of debris created by a ‘smart bomb.’ I had anticipated seeing a building with the roof caved in, not a crater the size of a municipal swimming pool.

Neighborhood residents were shoveling debris off their rooftops and clearing paths to their front doors through the wreckage, careful to avoid setting off any unexploded ordinances. In Maine, where I grew up, one clears snow at one’s front door and tries to avoid slipping; here, one clears rubble and tries to avoid being blown up.

Lebanese and Palestinian officials later claimed that a warship shelled the camp. The Israeli military claimed it was an aerial targeting of a house used by Hezbollah guerrillas.

This 6:30 am attack on Ain al-Hilweh destroyed a dozen or so cars, made a parking lot into a rubble field, wrecked several homes, injured five people, and killed a sanitation worker. At the time, I knew little of Ain al-Hilweh’s reputation as a militant stronghold, but I would wager that the death of the garbage collector did not bolster Israel’s security.

I did visit one house on the outer rim of the crater. Inside was a couple with their infant daughter. There was now a hole in their roof, and their walls and ceilings were webbed with cracks.

The infant smiled at me from her stroller. Her parents were sweeping up the rubble.

There was nothing to do but go on living.

Such devastation is difficult for most Americans to grasp. The closest our soil has come to this was 9/11, Oklahoma bombing, and our own hurricanes and earthquakes. Lebanon used to be the Riviera of the Middle East.

I still kick myself for missing out on a trip to Lebanon in 1999. I was a stock controller for 2 years, mostly in South Africa, but with nearby Lesotho, Swaziland and Namibia in the mix. In the company's declining era, they suddenly told me I was going to be sent to check on their other international branches. I got to go to Uganda, Egypt and Kenya, with an unexpected landing in Sudan (though I never left the airport). And then they told me they'd contracted a guy to do Nigeria, Zimbabwe and Lebanon. I felt betrayed that an outsider was stealing the trip I most wanted. Nevertheless, I had interesting experiences on my legs.