A chronicle of Cypriot boot camp. Intro HERE and last section HERE

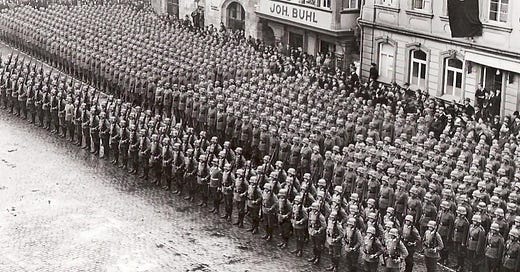

11. THE PARADE

Every day over the two weeks preceding the swearing-in ceremony, we practiced marching for the parade. It could have been learnt in thirty minutes, and we spent hours on it each day. We marched after breakfast; we marched at sunset; we marched in rain; we marched until our shoulders throbbed and the heel of our left boot soles wore away.

“I want to hear that left heel clip the ground!” Chewbacca would roar. “I don’t hear anything! That’s better! One-two, hep-two, hep-two, One! The elbows should be locked. The wrist locked down and the thumb pointed upwards! Your hand should swing up to eye level! One-two, hep-two, hep-two, One!”

After several days, they positioned us in our parade formations, arranged by platoon and height. I was in the first platoon and, being the tallest, was in the first line. I hoped I’d be tucked away within the formation as I didn’t want thousands of people to watch me march by like the Nutcracker. But there was no escaping it.

Grivas occasionally emerged from the headquarters building to examine our lack of progress. He always stood in the same place, an arm’s length away from our marching line, his expression stern and engrossed. One of my enduring memories from boot camp is the sight of my right arm swinging up and down like a windmill blade over a steadily enlarging Grivas, who’d be standing statuesquely on the other side of the painted white line along which we marched, his hands folded at his back, his sunglasses perched over his mustache, his motionless elevated face gazing down upon us as the sun slid behind him into the Mediterranean under a magnolia sky.

Grivas reveled in the marching. The sight of so many uniformed young men in a regimented parade elevated his spirit with manly passion. This was his version of self-realization, his flesh shuddering as it coursed with all that Hellenism and militarist exultation that gave meaning to his life as a training camp commander.

There was no slacking when it came to marching. Neither hail, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of Grivas’ sight stayed us from the dreary completion of our appointed rounds. The crucial thing in this boot camp was that we learned to march well. That was how you defended your country: you marched gloriously. We never did. Either the arphades were trying to sabotage Grivas’ dreams or they simply didn’t give a damn.

“You should be looking up when you march!” Grivas would lecture us. “Only women look down! Your eyes should look up, where the eagles fly.” The wind whipped across the plaza and we stood there, shivering, as he tried to inspire us.

“In hard times, you should raise your head and say, ‘I will struggle.’ To win the medal. Tomorrow it may be a small race. The day after tomorrow a marathon.”

“Up yours,” the kid next to me muttered.

“Who said that?” he screamed. “Tramp! Scumbag! Who told you to talk?!”

Grivas grew increasingly unstable with the approach of the swearing-in ceremony. “Lift your left knee high when I say attention or I’ll cut your legs off!” he bawled. “And don’t scratch yourselves!” His curses also grew increasingly obscene as boot camp progressed, filled with bizarre, often incomprehensible, references to genitalia.

On our last furlough before the swearing-in ceremony, Grivas made a round of the barracks rooms for an inspection. There were threats that we’d spend the weekend inside the camp if he was dissatisfied, and for once we took it to heart. We spent most of Friday morning scrubbing walls, washing windows, wiping the dust from the top of the ceiling fan blades, shining our boots, and stretching our blankets so tight that you could bounce a coin off the beds.

“He’s coming! He’s coming!” our barracks room captain cried, running into the room. We all stood at attention by our beds. We could hear him ranting in the room next to us. I later found out that he’d opened a locker and found the words “Fuck the commander” scribbled on the inside of the door.

He didn’t even glance at our room when he walked in. He went straight to the lockers and opened the first one. No one had expected he’d check lockers. The conscript with that locker stomped to attention and reported his name.

“Magazines… food…” Grivas murmured with disgust, tossing the magazine and the packet of chips onto the bed next to him.

He went to the next locker. “Dirty socks,” he said, tossing them behind him. He opened another locker and a soda tumbled out, spilling at his feet. He then opened my locker and began rummaging through my folded underwear, under which lay a plastic water bottle filled with zivania, a clear Cypriot brandy.

“Look at this, a bottle of water amidst the underwear. Couldn’t these be in a bag?”

“They’re clean,” I said.

His eyes darted over at me as if I had no right to speak. “If you come to my room in headquarters, you’ll see I keep all of my underwear and socks in bags.”

He shut the locker door and moved on to the next one.

Glad you did not get busted for the liquor in your locker. I am impressed that you fold your underwear.

Nutcracker or Pied Piper?

The sight of so many naked young women "in a regimented parade elevated [my] spirit with manly passion"