A primer on conscription

Pick at random a young man living in a nation without mandatory military service and, even if he’s averse to violence and authoritarianism, chances are at some point he’s entertained the thought of signing up. There are any number of reasons: sheer curiosity and a desire to see something of the world outside of one’s hometown, a guaranteed income and future university funding, naïve reveries about the heroism and glories of combat, and of course the desire to serve one’s country, which although much trumpeted is usually more bluster than patriotism, especially if the home team has a recent history of waging wars, not suffering them.

Most of those young men won’t sign up. Those who do are probably either so fired up about being soldiers or so short on other career options that they’ll tolerate more discipline and hardship than their counterparts in other countries who face mandatory military service. Assuming a country is large enough to be able to supply enough recruits, a volunteer army – which, patriotism aside, often amounts to a mercenary army of the poor – is more reliable than a conscript army. Drafted soldiers are less tolerant of privation and more prone to desertion because their ranks also include the middle class and, though far less so, the upper class.

The insubordination among American troops in Vietnam was in part due to the privileged economic position, at least when compared to volunteer soldiers, of many of the draftees. It’s no surprise that there’s barely any support by high-ranking U.S. military or political leaders to reinstate the draft. Conscripts are even more unruly when they feel there’s no justifiable reason for their service, or at least for its length. In this regard, the Cypriot National Guard makes for a particularly interesting case study.

A primer on the Cypriot military

When Cyprus gained independence from the British in 1960, its Constitution established a Cypriot army consisting of both Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot contingents. But as the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots weren’t integrated from the start, the army soon split on ethnic lines into two separate forces. After the 1963 hostilities between the two ethnic groups, the Cypriot National Guard – a purely Greek Cypriot military – was formed.

Conscription in the Cypriot National Guard currently stands at 12 months, down from 25 months prior to 2016, which made it the longest in the world along with countries like Iran, Egypt, Singapore, South Korea and Israel (North Korea, at around a decade, is in its own league). Though Cyprus has remained divided now for 50 years after the 1974 Greek coup and military invasion by Turkey, there has been no resumption of hostilities, aside from some rare and isolated killings on the Green Line in the first few decades of the division.

A primer on my conscription in the Cypriot military

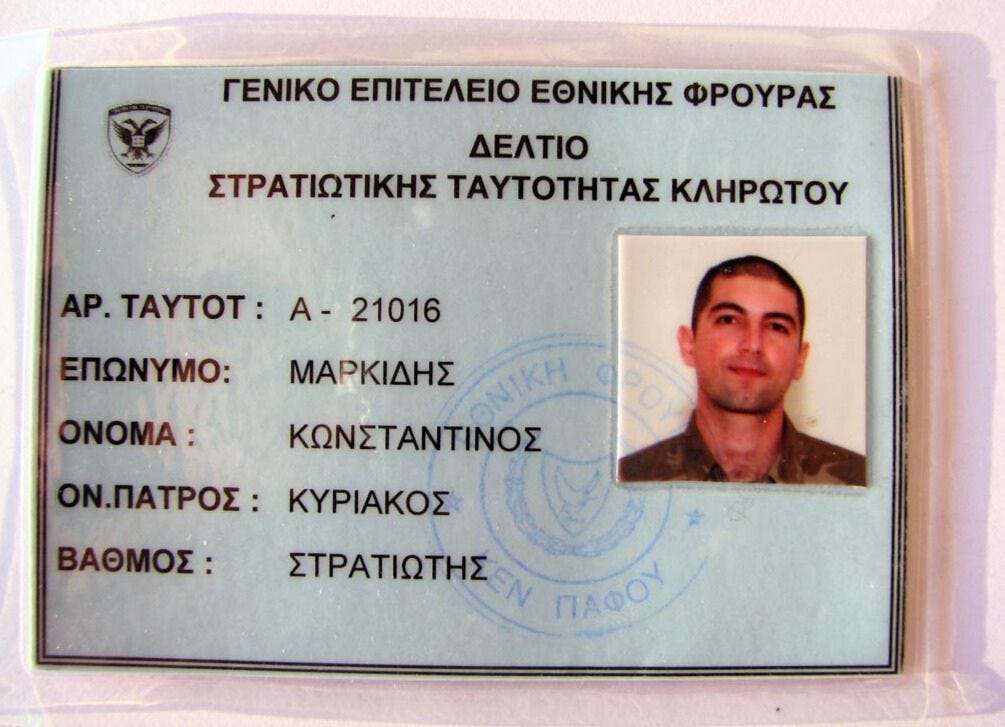

Though I’d spent five years of my boyhood in Cyprus, I was living in New York City when I turned of age to conscript (anyone with a Greek Cypriot father is obliged to serve). I visited Cyprus several times over the following decade, but it wasn’t until I moved to the island in 2005 that I was required by law to enlist within a two-year period.

Since I’d spent most of my life in the U.S. and was over the age of 26, I would only have to serve for three months instead of 25. In comparison to other Greek Cypriot conscripts my army term would be a weekend jaunt. Not to mention I would get to play G.I. Joe well into middle age. Until the age of 50 you are called up several times a year to button yourself back into uniform and go to firing practice or to sentry duty on the Green Line or to training on cover and concealment, which might include a nap under an olive tree somewhere.

So I enlisted on January 10, 2007. Technically, it was a conscription, but enlistment is closer to the truth. The army bureaucracy was too busy with coffee breaks, naps, and wet dreams of Hellenic consummation to keep tabs on me. I hadn’t been served any conscription papers, so I could have easily just not gone. Many, possibly even most, repatriated Cypriots evade their military duty. Just play dumb, don’t ever sign up, and if an official ever asks, say that you only recently arrived.

But I saw no good reason to avoid signing up. I despise war and its jingoist cheerleading, but I’m by no means a pacifist. More to the point, I didn’t want to miss out on any ethnographic fun.

Also, Cyprus may technically still be at a state of war (and in one of the longest ceasefires in modern history) but I also knew I had better odds of killing or getting killed on a weekend drive to the beach than while in the army. As for willingly subjecting myself to the commands and whims of any halfwit with a few stars and bars on his collar, as Moby Dick’s Ishmael said, “Who ain’t a slave? Tell me that.”

A primer on the point of this post

Starting Tuesday, I’ll be posting a rolling, serialized narrative of my time in the Cypriot army. I’ll post twice a week, on every Tuesday and Saturday. It was an unforgettable experience that didn’t transform me into the man that I’m not. Think Catch-22. Think Waiting for Godot. Think Dr. Strangelove or: How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb.

See you on Tuesday, the first day of boot camp. That’s when the fun begins.

That’s so crazy I actually had a short story idea for this, but in Lebanon.

I look forward to your series.

The division of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots within a new army sounds daft. Imagine if South Africa had created two armies in 1994, one white, one black.

I get the blur of conscription vs enlistment. I coincidentally made notes about that the other day. I was avoiding, but then enlisted for my conscription after Mandela was released. No blurriness when receiving the measly conscription salary which was worth about a daily (discounted) beer. I did 12 months, and later one or two one-month camps.